One day in March, 1984, I pulled my old Volkswagen into the town of Juchitan on the southern Mexican Isthmus of Tehuantepec. I expected to find a sleepy county seat off the highway, but I could feel tension in the air. I spotted several armed soldiers patrolling rooftops overlooking the municipal square. Local people, mostly Indigenous Zapotecs, were gathering with hand-made placards to protest the military occupation. I had been headed for El Salvador, still thirteen hours away by road, and was startled to see posters of Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero, assassinated in 1980. Emiliano Zapata, Pancho Villa and Our Lady of Guadalupe were the ubiquitous icons of Mexico. And now here was Romero, too.

I decided to stay for a couple of days and talk to people, and soon understood the connection. People here revered Romero as a saint, a man whose words supported their own struggles for justice.

Members of the “popular organizations” of the Juchitan municipalidad (pop. 1984: 70,000) had been teaching local peasant farmers to read and write. They formed cooperatives to buy seed and fertilizer in bulk and sell their products, working toward independence from local strongmen who monopolized land and commerce. A number of the groups had formed a common political platform and won local elections. They were moving away from the overarching national ruling party, the PRI (Party of the Institutionalized Revolution), working at what Romero had called in El Salvador, “the people’s project.” When the PRI refused to recognize the upstarts of Juchitan, Mexico City sent in the soldiers.

Since the 1960s, in other parts of Mexico, too, indeed all over Latin America, people were protesting a growing income gap between rich and poor caused by a new economic model. After World War II, encouraged by the United States and international banking organizations where Washington held sway, Latin nations undertook so-called development projects financed by heavy borrowing and a shift to industrializing agricultural production for export. In agricultural countries south of the Rio Grande, the majority who were small farmers was left behind. They languished on the land, or sold what they had to owners who could farm at a bigger scale to meet the demands of new government economic plans. Many were forced into densely populated “misery belts” around cities to work for low wages.

Sometimes reformers were murdered, or died when protests were met by gunfire from authorities, or they “disappeared” after being taken into custody or kidnapped by government agents or local henchmen.

The social landscape of Juchitan was similar in places farther South. By the 1980s half of the population of Latin America lived in poverty or extreme poverty, with little stake in the economic systems of their countries. In El Salvador, a tiny percentage of the population owned virtually all the land. Guatemala had given huge tracts to military officials, and most of the rest remained in the hands of traditional oligarchs. The vast majority of the population was left landless, condemned to a kind of serfdom on the land of others.

When Oscar Romero became archbishop of El Salvador in 1977, peasant farmers, union workers and students were already agitating for agrarian reform and other improvements to their lives through their own grassroots “popular organizations.” The archbishop was clear about supporting any associations or coalitions whose goal was social justice through peaceful means. Many of the organizations were Christian-inspired, drawing members from active parish communities, but the Church did not limit its support to those who were Catholic, Christian, or even legal. In a 1978 pastoral letter, considered the official word on a subject by a prelate, Romero wrote that Church teaching and tradition required speaking up when the faithful were faced with difficult times. “It would be wrong to remain silent,” the letter said. “The Church identifies with the poor when they demand their legitimate rights.”

Pictures of Romero had appeared in Juchitan because his words echoed there. In time I would discover that it was not unusual to find the image of the slain archbishop elsewhere in Latin America, well before the Vatican officially canonized him in 2018. Sometimes his head was already surrounded by a halo – a symbol of sainthood. His face gazed from convent walls and private chapels in Guatemala during its civil war (ended 1996), when public display might have been dangerous. In Bolivia, where tens of thousands of miners lost livelihoods in the collapse of the global tin market, catechists training in Cochabamba prayed for the intercession of Romero, at an altar graced with candles and his portrait. In a Peruvian chapel frequented by the Indigenous an unusual crucifix hung; in place of the customary figure of the dying Christ, there was a picture of Archbishop Romero.

In his martyrdom the prelate symbolized an ultimate act of support for grassroots efforts to change the status quo. His life and death resonated in an era when a global contest was taking place between the United States and the Soviet Union superpowers, first for world domination, and finally, to fix spheres of influence, while in the meantime, the people of Latin America were engaged in their own struggle, to change their lives for the better.

Romero exemplified the Latin American Cold War martyr, men and women who attested to their faith in the particular context of that period of history. During those years (1947-1989) the United States favored conservative regimes that would unwaveringly maintain the capitalist system. Even when they abused citizens’ rights, ultra-conservative governments, generally led by the military, were considered preferable to any sort of governments, the lesser of two evils. John F. Kennedy, fearing the spread of communism after the 1959 Cuban revolution, repeatedly referred to Latin America as “the most dangerous area in the world.” El Salvador was “a crazy place” and a “sick society” where there was ”too much indiscriminate killing,'' said a U.S. ambassador in San Salvador, Deane Hinton. “But if the other guys take over it would be a lot worse.'' As a hemispheric voice that spoke on behalf of the poor, denouncing U.S. intervention in national affairs and a U.S.-backed government that ruled by repression, Oscar Romero was a threat and needed to be silenced.

At first Washington attempted to quiet Romero by diplomatic means. In January 1980, U.S. Secretary of State Zbigniew Brzezinski wrote to John Paul II, a fellow Pole who had ascended to the papal throne less than two years before, requesting the pope’s “intervention.” The archbishop was critical of the Salvadoran ruling junta which Washington considered the “best hope” for the country, Brzezinski wrote, without mentioning that the junta failed to stop murders of civilian social activists. Despite warnings to Romero “and his Jesuit advisors” Brzezinski wrote that the archbishop “leaned toward support for the extreme left.” This was not true.

The pope did not express support for Romero at the time, which confounded and hurt him. But instead of being silenced, he raised his voice more as violence grew.

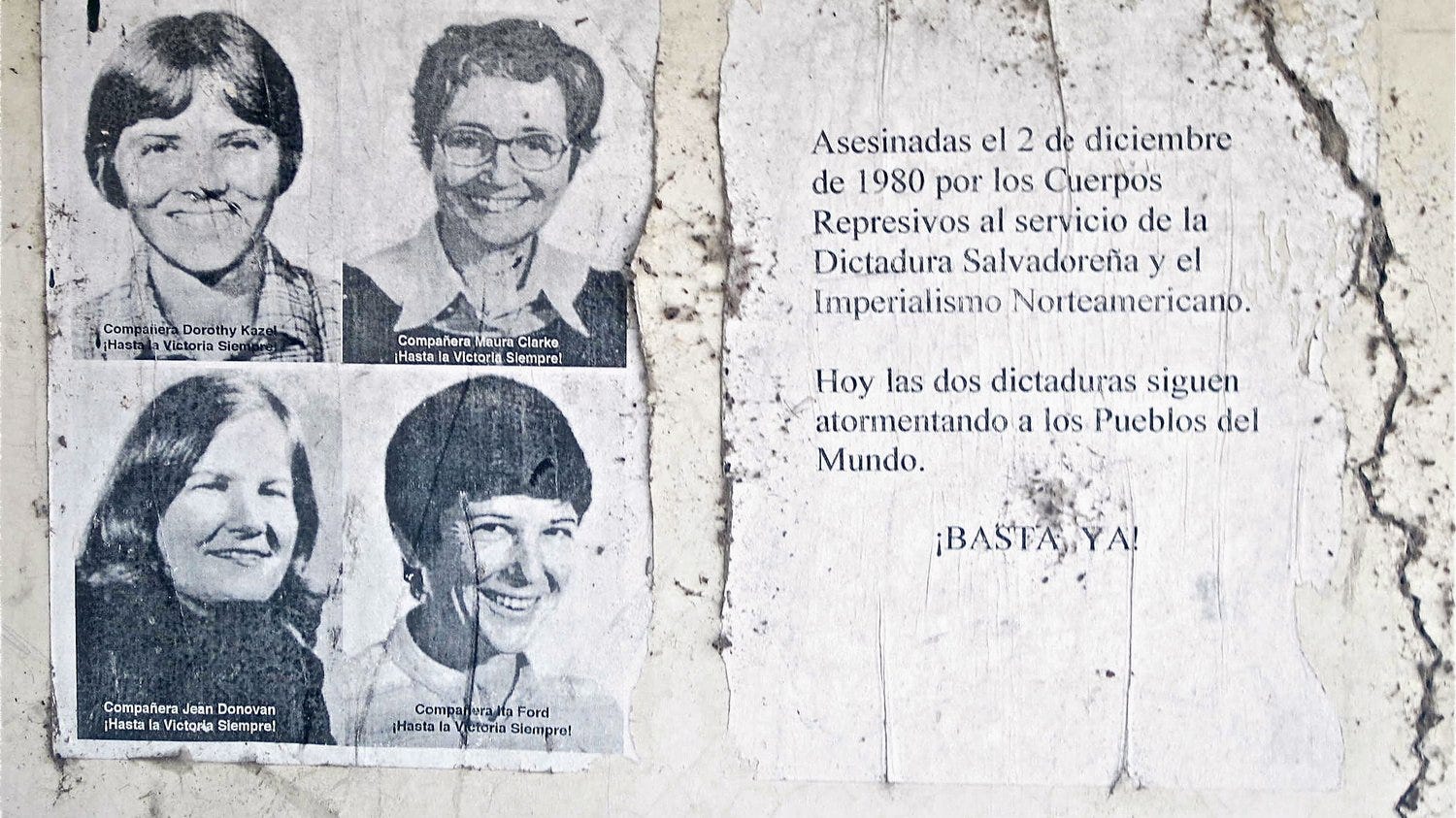

Washington knew that death squads were connected to the U.S.-supported Salvadoran military; they were not “rogue elements” that operated independent of the state, the official story. The assassination teams had begun operating the 1970s, military men who put on plain clothes for the operations, or civilians sent by military officers to execute targets. The government organized a rural paramilitary with its own hit teams. In town and country, squads killed peasant farmers organizing for land reform, labor union and student leaders, and religious workers who supported them. The system was an effective tool in a war against a civilian population that was energetically developing groups that aimed for change by non-violent means. Out of the continued repression of the civilian movement an armed guerrilla response emerged late in 1980, but neither government troops nor rebels were able to defeat the other militarily. The death squads carried on, killing activists and other community leaders to frighten and dishearten civilians.

The archbishop was a peaceful man who continually called for dialogue and reconciliation, but never failed to defend the poor. He said insurrection was legitimate when all other forms of self-defense had failed. Given the death squad strategy based on the psychological effect of selective assassination, Romero was an eminently logical target. When I covered El Salvador during the war, I heard an echo of despair in the voices of people who asked, “If they can kill an archbishop, what can’t they do?”

A report declassified in 1993 shows that the State Department knew soon after Romero’s death that the crime had been plotted during a meeting organized by Roberto D’Aubuisson, a cashiered intelligence officer trained at the U.S. School of the Americas. Participants “drew lots” to see who would pull the trigger, according to the report. But the U.S. authorities did not divulge the information during a Salvadoran government investigation into the archbishop’s murder, which never reached the courts. Neither did State Department officials share what they knew about the death squads during testimony before Congress on human rights in El Salvador; invariably, they presented the country as a bastion against communism. Assured of the El Salvador’s adherence to norms, Congress continued to certify the flow of U.S. military and economic aid.

Robert White, the U.S. ambassador when Romero was killed, later told the New York Times, "The Salvadoran military knew that we knew, and they knew when we covered up the truth, it was a clear signal that, at a minimum, we tolerated this." Hiding the facts on Romero’s assassination, and the murders of others, helped to give free reign to bad actors in the twelve-year war that ended in 1992. Seventy-five thousand died, mostly civilians at government hands.

Of all the things he was in life – pastor, theologian, prelate of the Salvadoran Church -- Oscar Romero had posed the most dangerous threat to the powerful because he was a prophet in the Old Testament tradition of Ezekiel, Jeremiah and Isaiah, who condemned growing disparity between the few rich and many poor, and warned against false gods. He warned against idolizing wealth, and false religiosity, quoting Amos (5:21-24): “Spare me the sound of your hymns, and let me not hear the music of your lutes. But let justice well up like water, righteousness like an unfailing stream.” Like the Old Testament prophets who decried Pharaoh for repressing God’s people, Romero spoke clearly to the government and military, as he did in the sermon the day before he died when he called on them “in the name of God” to “stop the repression.” As the Salvadoran theologian Jon Sobrino has written, Romero “began with God, but he spoke of history, and therefore, he also spoke of things secular.” It was the latter, wrote Sobrino, “that formally constituted him a prophet.” For all of Romero’s connection to the tradition of the Old Testament, the archbishop was a prophet of his particular day, alert to its concrete “signs of the times” -- political violence, cries for justice, the layers of pressure, including from abroad, that weighed down on the Salvadoran people.

Like African Americans who live with a history of slavery that permeates generations to the present day, dissident groups in Latin America carry with them a history of U.S. imperialism. In the twentieth century alone the United States sent warships (“gunboat diplomacy”), or aircraft, or landed troops, forty-seven times in thirteen Latin countries to protect U.S. business interests and friendly regimes. As a Cold War prophet, Romero called forth a nation’s right to self-determination, a right highlighted in the final document of the landmark Medellin conference of Latin American Bishops (1968) which pledged to “denounce the unjust action of world powers that works against self-determination of weaker nations who must suffer the bloody consequences of war and invasion.” Latin Americans who opposed the status quo perceived U.S. military and economic domination as the enemy that impeded the free development of political and economic systems apt to the region, an enemy worth fighting against.

In February 1980, Romero wrote to President Jimmy Carter, imploring him not to send U.S. advisors or more war materiel to El Salvador where “political power is in the hands of unscrupulous military officers who know only how to repress the people and favor the interests of the oligarchy.” The people were “awakening and organizing and have begun to prepare themselves” to manage the country’s future, Romero wrote in a passage tinged with hope. In other writing and interviews the archbishop was saying the “people’s project” was on the verge of unification and success, ready to achieve non-violent change. He appealed to Carter’s “religious sentiments” and “feelings in defense of human rights” to guarantee that the United States would not intervene to “frustrate the Salvadoran people, to repress them and keep them from deciding autonomously the economic and political course that our nation should follow.” He wanted the future of the country to remain in the hands of Salvadorans, not outsiders, and quoted from the document of the important meeting of Latin American bishops that he had attended just the year before, in Puebla, Mexico, “when we spoke of the legitimate self-determination of our peoples, which allows them to organize according to their own spirit and the course of their history and to cooperate in a new international order.” At the time, the term “new international order” echoed an aspiration among the poorer countries of the global South for economic and political cooperation with each other that might free them from the hegemony of the global superpowers.

But a new international order was not something that superpowers wanted. Romero received no response from President Carter. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance answered Romero’s letter stating that Washington considered the Salvadoran government “moderate and reformist,” and that supporting the junta would be the best way of promoting rights. Soon U.S. aid and weapons began to flow in a torrent, continuing under President Reagan, and under George H.W. Bush, when the ultra-right National Republican Alliance party founded by D’Aubuisson, the death squad leader, won the national elections.

Oscar Romero had been the ideal death squad target of the place and time. He represented in a single person the morally based opposition to the reigning authority, the victim whose death would generate the most fear among a rebellious population. But instead of being cowed by his murder, Salvadorans, and other Latin Americans under siege in the heat of the Cold War, took heart in the archbishop as a symbol of their struggle, regarding him as a martyr, revering him as a prophet for his time, even as political reverses crushed progress toward immediate liberation from lives of poverty and strife.

Coming upon Romero’s image by surprise all those years ago in Juchitan, then finding it appear elsewhere, showed me that it is not the Vatican that makes saints, people do. Shortly before his death, Romero told a reporter “in all humility” that, “if they kill me, I will rise among the Salvadoran people.” Knowing his picture hung in places far from El Salvador, I concluded that people in every age and in all places, especially in the most dangerous times, know in whom to put their trust, and hope, with or without official approbation.

The life models we emulate and admire change with history, according to the needs of the times. Oscar Romero is properly called a martyr, and not only by ordinary people expressing popular religiosity. He is a martyr in the sense of the word that developed along with the movement articulated at the Medellin conference, to commit the Church to an option for the poor. His martyrdom was not officially recognized at first: ultra-conservative hierarchy, including in El Salvador, knew full well that identification with the poor was considered subversive in Latin America, and pigeon-holed the sainthood process for Romero until Pope Francis moved it forward.

With Romero’s canonization, however, no longer could the Vatican entertain the cry of critics that Romero was not a saint, but a victim of political tension. Because theology is not static, either. It develops within cultural and historical contexts as it responds to the questions of who is God and what is the relation of God to history. Theology recognizes that culture, history and contemporary thought are to be considered along with scripture and tradition, as valid sources for theological expression. During the Cold War the Latin American Church had become identified with the struggle for fairness for the poor in this world through the practice of liberation theology, which examines the meaning of religious faith and action in the context of oppression and inequality. Romero personified the revolutionary theology. He was known as “the voice of those without a voice,” adamantine in his call for justice for the most vulnerable.

Just as liberation theology gave a new dimension to Christian theology, so too did Cold War Latin America give a new dimension to martyrology. Traditionally a “martyr” was considered someone who dies while standing up against hatred of the Catholic faith, odium fidei. But Catholics were the majority population in Latin America during the 1980s, and Romero’s assassins were hardly crusading against the religion into which they had been baptized. The faith as professed by Romero had become synonymous, in historically important sectors, with the demand for justice for the poor, so that the archbishop can be said to have expanded the definition of who is a martyr, a person with an exemplary life killed out of odium justiciae, hatred of justice.

Since the end of the Cold War, without deep structural change of the kind in which Archbishop Romero and the popular organizations of El Salvador once placed their expectations, the promises of peace and democracy have not brought better living conditions to the majority in Latin America, and the poverty rate is climbing again. Economic experts forecast, as one journal put it delicately, “a more precarious life for millions of Latin Americans compared to before the pandemic.” As long as the poor, the landless and homeless, and those who struggle against discrimination and early death are with us, and there exist prophetic voices to denounce them, the age of martyrs is not over.