During the U.S.-backed wars in Central America, I met parents whose children were whisked off by U.S.-backed militaries, never to be seen by their families again. President Biden’s new task force created to find parents of children taken at the border under Trump’s “zero tolerance” policy, can learn lessons from those historic separations: Despite best intentions, the harm cannot be undone. And beware of Central American governments, which have protected adoptions of children irregularly taken from their parents–- partner instead with highly motivated private groups.

On an autumn morning in 1985, Niris Menjivar, then 41, showed me the last place he had seen his daughter, Reina, 11, three weeks before. “Do you think she will know she is not an orphan?” he asked. We were in territory held by leftist rebels, supported by peasant farmers like Menjivar who had long suffered at the hands of an abusive government, and were suffering even moreacutely from bombardment since Washington began supplyingair power to San Salvador. When local people feared a government military operation, they packed food and infants on their backs and fled to remote mountain corners on treks they called guindas.On the last guinda,returning with other men carrying water to where women and children sheltered, Menjivar said he watched helplessly from behind a boulder, unable to cry out without giving away the hiding place of neighbors as a military helicopter lifted off with his daughter, and soldiers captured others.

“Do you understand?” he asked, as if asking forgiveness.

“The torture is ongoing,” Adriana Portillo-Bartow of Chicago, a retired community services worker, told me recently. In 1980, Portillo-Bartow’s daughters Glenda, 9, and Rosaura, 10, and her 18-month old half-sister, Alma, were taken in a military raid from a house suspected as a hideout for rebels in Guatemala. She never saw them again.

Portillo-Bartow has worked for Amnesty International, and testified in courts and to a truth commission about missing Guatemalan children. The Guatemala government targeted families thought to favor rebels “as a way to deter others,” she said. Trump used the “same logic, the same kind of sadistic policy planned to cause damage, punishment for coming to the United States.”

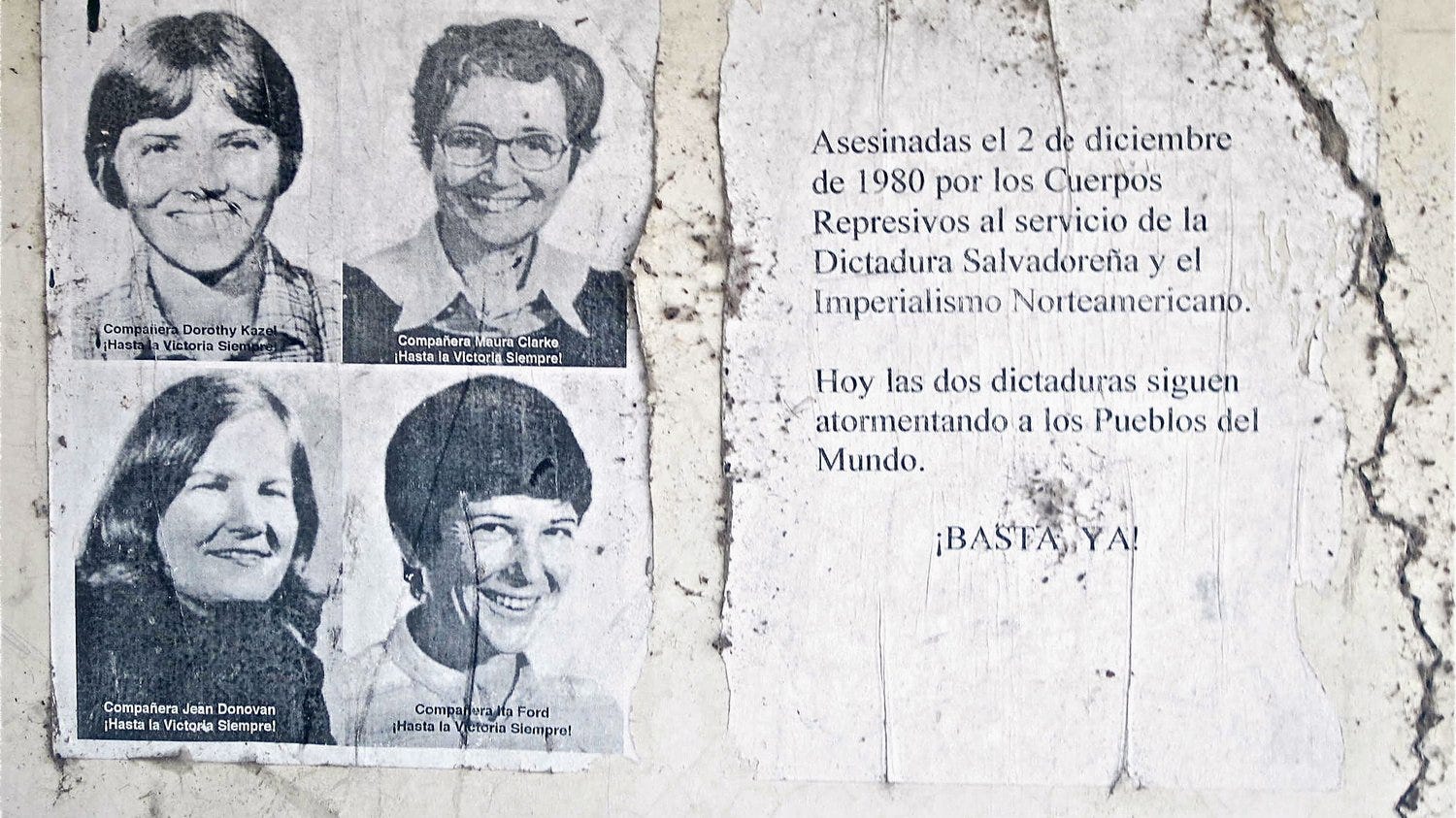

At least 3000 children went missing during the war in El Salvador; five thousand went missing in Guatemala. Neither government pursued reunions. Those thattake place largely have been organized largely by private groups, such as one founded by a Jesuit priest in El Salvador, another by mental health advocates in Guatemala, more by organizations of the once-missing children – now adults – in the United States and Europe.

In 2000, Luis Curruchich, then 48, pictured above, sat in a wooden chair outside his house in Santa Anita Las Canoas, Guatemala, and told me he was still lamenting the loss of his daughter, Aura Marina, who had disappeared at age three during a 1980 army attack on his village. “She would be 23 now,” he said.

A Guatemalan Catholic Church report said missing children were taken to army bases before being given to soldiers and officers, or placed in orphanages or trafficked into adoptions; guerrillas took two adolescent boys to join their ranks. Americans adopted more than 30,000 Guatemalan children from those years until 2008, when a corrupt adoption system was closed down for reforms. In Honduras, a hotel clerk offered me an “adopting baby” rate as I checked in with my San Francisco-born 6-month old one day in 1987 – I found the place filled with foreigners waiting to adopt. An estimated 2,354 Salvadoran children were adopted into the United States during the war (1980-1992). Adoption also may be the destiny of the misplaced children of the border captures. A 2018 Associated Press investigation identified “holes” in the U.S. legal system that permitted granting legal custody to families caring for migrant children without notifying the children’s parents. Some were separated during the Obama administration which deported three million persons.

Gemma Givens, a founder of Next Generation, an association of Guatemalan adoptees in nineteen countries who are looking for their birth families (and sometimes find them), told me the children separated recently at the border will need “emotional support” if their parents are not found despite the task force’s efforts, and the, too, want to search some day.Immigration hardliners amenable to family separation remain working in the new administration. The cycle of Central American children torn from their parents seems endless. “It has to stop,” Portillo-Bartow said.

White House image:

photo of Luis Curruchich by Nancy McGirr copyright 2000 for the San Francisco Chronicle